|

|

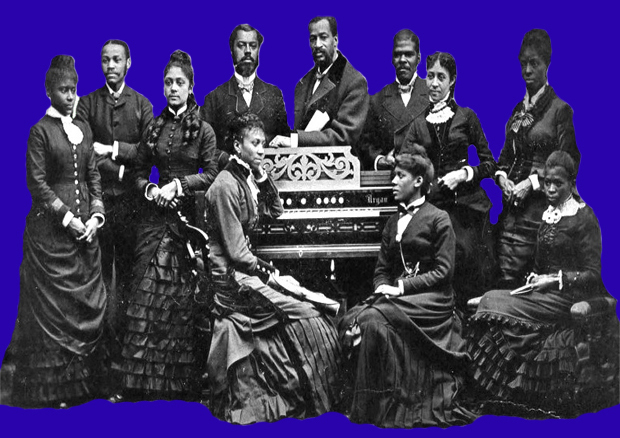

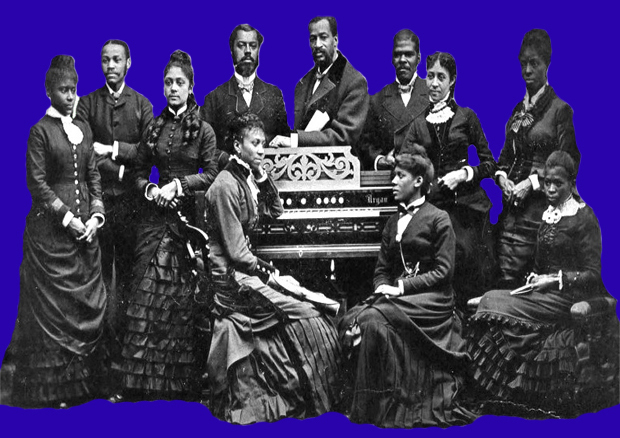

The Fisk Jubilee Singers |

|

|

|

The Fisk Jubilee Singers |

|

|

|

| African American Spirituals A National Treasure | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

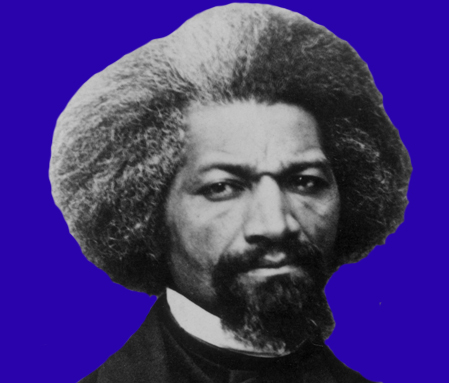

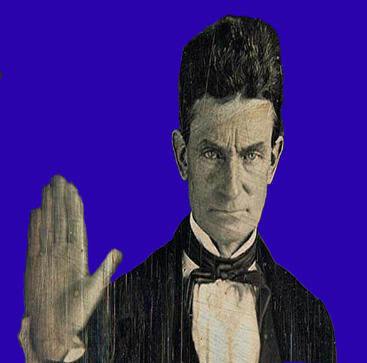

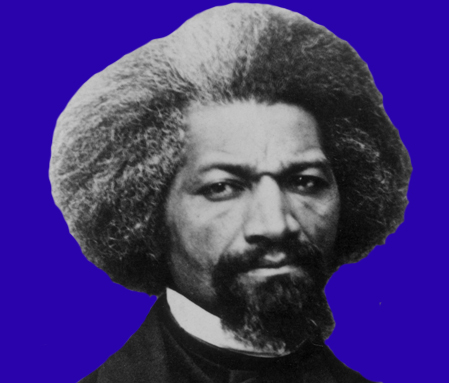

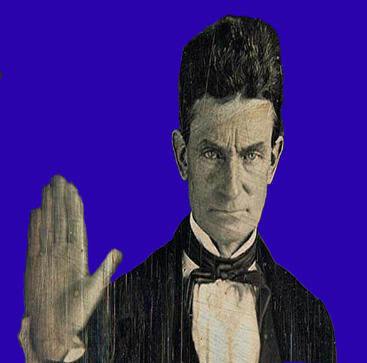

| William Lloyd Garrison | Frederick Douglass | John Brown |

| African American Spirituals |

| A National Treasure |

From 1619 to 1865, enslaved African Americans created their own unique form of expression known today as African American Spirituals. As African Americans were not allowed to speak their native languages or play African instruments, African American Spirituals incorporated into the English language and the Christian religious faith.

Simply defined, African American Spirituals are the songs created and first sung by African Americans during the times of slavery. These songs are celebrated as a American National Treasure. For they are the source for which gospel, jazz and blues evolved.

The lyrics of these songs are tightly linked with the lives of their authors who were inspired by the message of God and the gospel of the Bible. The most pervasive message conveyed by African American Spirituals is that of an enslaved people for yearning to be set free. The slaves believed they understood better than anyone what freedom truly meant in both a spiritual and a physical sense.

The Old Testament scriptures that are referenced in their songs spoke of deliverance in this world and they believed God would deliver them from bondage. These spirituals are different from hymns and psalms because the African American slave used them as a way of sharing the hard condition of being a slave while also singing about their love and faith in God.

The African American slave was forbidden to learn how to read and write. They had to find ways to communicate secretly. African American Spirituals were a medium for several layers of communication and meaning

African American Spirituals where the strong oral tradition of songs, stories proverbs and historical accounts. African American Spirituals have been apart of American culture from times of slavery to today and their legacy is clear in today’s gospel music. African American Spirituals where also sung during the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960’s. Songs that we are familiar with such as "We Shall Overcome" and "Marching Round Selma were heard in the south to united African American in the struggle for civil rights.

Some of the more commonly known songs including "Swing Low Sweet Chariot" and "The Gospel Train", used language which described activities but had a second meaning relating to the underground railroad.

The lyrics used in African American Spirituals became a metaphor from freedom of slavery and they were a secret way for slaves to communicate with each other, teach there young, record there history and heal there pain.

Frederick Douglas a fugitive slave who became one of the United States leading abolitionist stated that African American Spirituals told a tale of woe which was all together beyond feeble comprehension and that every tone was a testimony against slavery and a prayer to God for deliverance from chains.

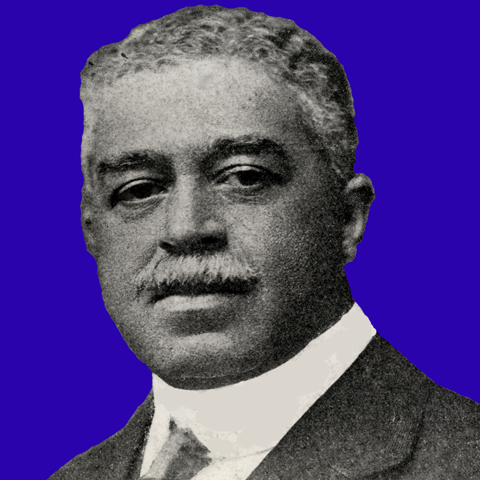

| Harry T Burleigh |

| December 2, 1866 to September 12, 1949 |

African American Classical Composer, Arranger and Professional Singer

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Harry T Burleigh

For more than 200 years, slavery was legal in the present boundaries of the United States. A country founded on the belief that all men are created equal with the God given right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. With one third (1/3) of its populations living in slavery, the United States would partake in one of history great ironies. Its incarcerated inhabitants, a nation enslaved would write the countries first folk music and sing the nations first songs of freedom.

Millions of voices and centuries of toil will rise up and become one voice and that voice will create a musical genre to which all American songs could trace their lineage and their roots.

Although his name is relatively unknown, Harry Thacker Burleigh (named Henry after his father) born on December 2, 1866 in Erie Pennsylvania.

Music was everywhere in the Burleigh’s home. His father Henry Burleigh who died when Harry was a child would lead the family in singing while they worked. His grandfather formerly enslaved was the town crier and lamp lighter and would take Harry and his older brother Reginald with him on his nightly rounds. Grandfather and grandsons would sing the songs of the African slave. The songs that the grandfather’s father and his grandfather sang songs of life and freedom.

Harry’s mother Elizabeth Burleigh and her sister Louisa taught him the songs of the European classical tradition. Elizabeth Burleigh was a college-educated woman fluent in both French and Greek. But in the early days of emancipation she was only able to get a job as a janitor and housemaid. She and her son Harry worked in the home of Elizabeth Russell a local arts patron who hosted performances of art songs. Young Harry would listen from a distance and the songs and singers he heard in Elizabeth Russell’s home help release his inner voice. A deep and rich baritone voice that was soon in demand at churches synagogues and homes in and around Erie Pennsylvania.

In 1892, Harry T Burleigh left Erie Pennsylvania to pursue a musical career. With only a few belongings an a head full of music, Harry T Burleigh traveled to New York City to audition for the National Conservatory of Music.

The years Harry T Burleigh spent at the Conservatory greatly influenced his career mostly due to his friendship with Antonin Dvorák the Conservatory’s director. After spending countless hours recalling and performing the African American Spirituals that he had learned from his grandfather, Harry was encourage to preserve these songs in his on arrangements and their themes could be heard in Antonin Dvorák’s new world symphony.

Before the turn of the century Harry T Burleigh established himself as a composer of popular art songs. For decades Harry T Burleigh traveled the world performing the songs of his grandfather all the while giving his country it’s first song which became jazz, swing, blues and eventually rock.

Harry T Burleigh died on September 12, 1949 and was buried in Erie Pennsylvania.

| Harry T Burleigh |

| December 2, 1866 to September 12, 1949 |

African American Classical Composer, Arranger and Professional Singer

African American Spirituals Videos

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| African American Spirituals |

| Instrumentals |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| African American Spirituals |

| A National Treasure |

| African American Spirituals A National Treasure | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

| William Lloyd Garrison | Frederick Douglass | John Brown |

Buy African American Spirituals

| African American Spirituals |

| A National Treasure |

| African American Spirituals A National Treasure | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

African American Spirituals © 2014 - 2022 All Rights Reserved |

African American Spirituals A National Treasure |