|

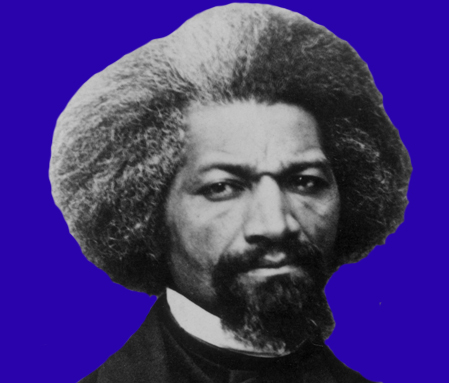

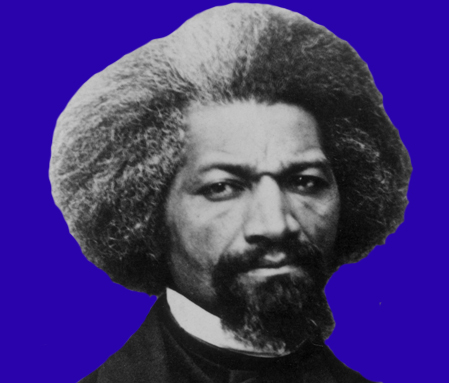

Frederick Douglass |

|

|

Narrative of the life of Frederick Douglas,

An American Slave published in 1845 (20 years before the Emancipation Proclamation)

I was born in Tuckahoe, near Hillsborough, and about

twelve miles from Easton, in Talbot county, Maryland. I have no accurate

knowledge of my age never having seen any authentic record containing it.

By far the larger part of the slaves know as little of their ages as horse know

of theirs, and it is the wish of most masters within my knowledge to keep their

slaves thus ignorant. I do not remember to have ever met a slave who could

tell of his birthday. They seldom come nearer to it than planting-time.

A want of information concerning my own was a source of unhappiness to me even

during childhood. The white children could tell their ages. I could

not tell why I ought to be deprived of the same privilege. I was not

allowed to make any inquires of my master concerning it. He deemed all

such inquires on the part of a slave improper and impertinent, and evidence of a

restless spirit. The nearest estimate I can give makes me now between

twenty-seven and twenty-eight years of age. I come to this, from hearing

my master say, some time during 1835, I was about seventeen years old.

My mother was named Harriet Bailey. She was the

daughter of Isaac and Betsey Bailey, both colored, and quite dark. My

mother was of darker complexion than either my grandmother or grandfather.

My father was a white man. He was admitted to be such by all I ever heard speak of my parentage. The opinion was also whispered that my master was my father; but of the correctness of this opinion, I know nothing; the means of knowing was withheld from me. My mother and I were separated when I was but an infant – before I knew her as my mother. It is a common custom, in the part of Maryland from which I ran away, to part children from their mothers at a very early age. Frequently, before the child has reached its twelfth month, its mother is taken from it, and hired out on some farm a considerable distance off, and the child is placed under the care of an old woman, too old for field labor. For what this separation is done, I do not know, unless it be to hinder the development of the child’s affection of the mother, and to blunt and destroy the natural affection of the mother for the child. This is the inevitable result.

I never saw my mother, to know her as such, more than four or five times in my life; and each of these times was very short in duration, and at night. She was hired by a Mr. Stewart, who lived about twelve miles from my home. She made her journeys to see me in the night, traveling the whole distance on foot, after the performance of her day’s work. She was a field hand, and a whipping is the penalty of not being in the field at sunrise, unless a slave has special permission from his or her master to the contrary – a permission which they seldom get, and one that gives to him that gives it the proud name of being a kind master. I do not recollect of ever seeing my mother by the light of day. She was with me in the night. She would lie down with me, and get me to sleep, but long before I waked she was gone. Very little communication ever took place between us. Death soon ended what little we could have while she lived, and with it her hardships and suffering. She died when I was about seven years old, on one of my master’s farms near Lee’s Mill. I was not allowed to be present during her illness, at her death, or burial. She was gone long before I knew any thing as bout it. Never having enjoyed, to any considerable extent, her soothing presence, her tender and watchful care, I received the tidings of her death with much the same emotions I should have probably felt at the death of a stranger.

Called thus suddenly away, she left me without the slightest intimation of who my father was. The whisper that my master was my father, may or may not be true; and, true or false, it is of but little consequence to my purpose whilst the fact remains, in all its glaring odiousness, that slaveholders have ordained, and by law established, that the children of slave women shall in all cases follow the condition of their mothers; and this is done too obviously to administer to their own lusts, and make a gratification of their wicked desires profitable as well as pleasurable; for by this cunning arrangement the slaveholder, in cases not a few, sustains to his slave the double relation of master and father.

I know of such cases; and it is worthy of remark that such slaves invariably suffer greater hardships, and have more to contend with, than others. They are, in the first place, a constant offence to their mistress. She is ever disposed to find fault with them; they can seldom do any thing to please her; she is never better pleased than when she sees them under the lash, especially when she suspects her husband of showing to his mulatto children favors which he withholds from his black slaves. The master is frequently compelled to sell this class of his slaves, out of deference to the feelings of his white wife; and, cruel as the deed may strike any one to be for a man to sell his own children to human flesh-mongers, it is often the dictate of humanity for him to do so; for, unless he does this, he must not only whip them himself, but must stand by and see one white son tie up his brother, of but few shades darker complexion than himself, and ply the gory lash to his naked back; and if he lisp one word of disapproval, it is set down to his parental partiality, and only makes a bad matter worse, both for himself and the slave whom he would protect and defend.

"The Meaning of July Fourth for the Negro"

Fellow Citizens, I am not wanting in respect for the fathers of

this republic. The signers of the Declaration of Independence were brave men.

They were great men, too ‹ great enough to give frame to a great age. It does

not often happen to a nation to raise, at one time, such a number of truly great

men. The point from which I am compelled to view them is not, certainly, the

most favorable; and yet I cannot contemplate their great deeds with less than

admiration. They were statesmen, patriots and heroes, and for the good they did,

and the principles they contended for, I will unite with you to honor their

memory....

...Fellow-citizens, pardon me, allow me to ask, why am I called upon to speak

here to-day? What have I, or those I represent, to do with your national

independence? Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural

justice, embodied in that Declaration of Independence, extended to us? and am I,

therefore, called upon to bring our humble offering to the national altar, and

to confess the benefits and express devout gratitude for the blessings resulting

from your independence to us?

Would to God, both for your sakes and ours, that an affirmative answer could be

truthfully returned to these questions! Then would my task be light, and my

burden easy and delightful. For who is there so cold, that a nation's sympathy

could not warm him? Who so obdurate and dead to the claims of gratitude, that

would not thankfully acknowledge such priceless benefits? Who so stolid and

selfish, that would not give his voice to swell the hallelujahs of a nation's

jubilee, when the chains of servitude had been torn from his limbs? I am not

that man. In a case like that, the dumb might eloquently speak, and the "lame

man leap as an hart."

But such is not the state of the case. I say it with a sad sense of the

disparity between us. I am not included within the pale of glorious anniversary!

Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The

blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. The rich

inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your

fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought light and

healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth July is yours,

not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. To drag a man in fetters into the grand

illuminated temple of liberty, and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems,

were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony. Do you mean, citizens, to mock me,

by asking me to speak to-day? If so, there is a parallel to your conduct. And

let me warn you that it is dangerous to copy the example of a nation whose

crimes, towering up to heaven, were thrown down by the breath of the Almighty,

burying that nation in irrevocable ruin! I can to-day take up the plaintive

lament of a peeled and woe-smitten people!

"By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down. Yea! we wept when we remembered

Zion. We hanged our harps upon the willows in the midst thereof. For there, they

that carried us away captive, required of us a song; and they who wasted us

required of us mirth, saying, Sing us one of the songs of Zion. How can we sing

the Lord's song in a strange land? If I forget thee, 0 Jerusalem, let my right

hand forget her cunning. If I do not remember thee, let my tongue cleave to the

roof of my mouth."

Fellow-citizens, above your national, tumultuous joy, I hear the mournful wail

of millions! whose chains, heavy and grievous yesterday, are, to-day, rendered

more intolerable by the jubilee shouts that reach them. If I do forget, if I do

not faithfully remember those bleeding children of sorrow this day, "may my

right hand forget her cunning, and may my tongue cleave to the roof of my

mouth!" To forget them, to pass lightly over their wrongs, and to chime in with

the popular theme, would be treason most scandalous and shocking, and would make

me a reproach before God and the world. My subject, then, fellow-citizens, is

American slavery. I shall see this day and its popular characteristics from the

slave's point of view. Standing there identified with the American bondman,

making his wrongs mine, I do not hesitate to declare, with all my soul, that the

character and conduct of this nation never looked blacker to me than on this 4th

of July! Whether we turn to the declarations of the past, or to the professions

of the present, the conduct of the nation seems equally hideous and revolting.

America. is false to the past, false to the present, and solemnly binds herself

to be false to the future. Standing with God and the crushed and bleeding slave

on this occasion, I will, in the name of humanity which is outraged, in the name

of liberty which is fettered, in the name of the constitution and the Bible

which are disregarded and trampled upon, dare to call in question and to

denounce, with all the emphasis I can command, everything that serves to

perpetuate slavery ‹ the great sin and shame of America! "I will not equivocate;

I will not excuse"; I will use the severest language I can command; and yet not

one word shall escape me that any man, whose judgment is not blinded by

prejudice, or who is not at heart a slaveholder, shall not confess to be right

and just.

But I fancy I hear some one of my audience say, "It is just in this circumstance

that you and your brother abolitionists fail to make a favorable impression on

the public mind. Would you argue more, an denounce less; would you persuade

more, and rebuke less; your cause would be much more likely to succeed." But, I

submit, where all is plain there is nothing to be argued. What point in the

anti-slavery creed would you have me argue? On what branch of the subject do the

people of this country need light? Must I undertake to prove that the slave is a

man? That point is conceded already. Nobody doubts it. The slaveholders

themselves acknowledge it in the enactment of laws for their government. They

acknowledge it when they punish disobedience on the part of the slave. There are

seventy-two crimes in the State of Virginia which, if committed by a black man

(no matter how ignorant he be), subject him to the punishment of death; while

only two of the same crimes will subject a white man to the like punishment.

What is this but the acknowledgment that the slave is a moral, intellectual, and

responsible being? The manhood of the slave is conceded. It is admitted in the

fact that Southern statute books are covered with enactments forbidding, under

severe fines and penalties, the teaching of the slave to read or to write. When

you can point to any such laws in reference to the beasts of the field, then I

may consent to argue the manhood of the slave. When the dogs in your streets,

when the fowls of the air, when the cattle on your hills, when the fish of the

sea, and the reptiles that crawl, shall be unable to distinguish the slave from

a brute, then will I argue with you that the slave is a man!

For the present, it is enough to affirm the equal manhood of the Negro race. Is

it not astonishing that, while we are ploughing, planting, and reaping, using

all kinds of mechanical tools, erecting houses, constructing bridges, building

ships, working in metals of brass, iron, copper, silver and gold; that, while we

are reading, writing and ciphering, acting as clerks, merchants and secretaries,

having among us lawyers, doctors, ministers, poets, authors, editors, orators

and teachers; that, while we are engaged in all manner of enterprises common to

other men, digging gold in California, capturing the whale in the Pacific,

feeding sheep and cattle on the hill-side, living, moving, acting, thinking,

planning, living in families as husbands, wives and children, and, above all,

confessing and worshipping the Christian's God, and looking hopefully for life

and immortality beyond the grave, we are called upon to prove that we are men!

Would you have me argue that man is entitled to liberty? that he is the rightful

owner of his own body? You have already declared it. Must I argue the

wrongfulness of slavery? Is that a question for Republicans? Is it to be settled

by the rules of logic and argumentation, as a matter beset with great

difficulty, involving a doubtful application of the principle of justice, hard

to be understood? How should I look to-day, in the presence of Americans,

dividing, and subdividing a discourse, to show that men have a natural right to

freedom? speaking of it relatively and positively, negatively and affirmatively.

To do so, would be to make myself ridiculous, and to offer an insult to your

understanding. There is not a man beneath the canopy of heaven that does not

know that slavery is wrong for him.

What, am I to argue that it is wrong to make men brutes, to rob them of their

liberty, to work them without wages, to keep them ignorant of their relations to

their fellow men, to beat them with sticks, to flay their flesh with the lash,

to load their limbs with irons, to hunt them with dogs, to sell them at auction,

to sunder their families, to knock out their teeth, to burn their flesh, to

starve them into obedience and submission to their masters? Must I argue that a

system thus marked with blood, and stained with pollution, is wrong? No! I will

not. I have better employment for my time and strength than such arguments would

imply.

What, then, remains to be argued? Is it that slavery is not divine; that God did

not establish it; that our doctors of divinity are mistaken? There is blasphemy

in the thought. That which is inhuman, cannot be divine! Who can reason on such

a proposition? They that can, may; I cannot. The time for such argument is

passed.

At a time like this, scorching irony, not convincing argument, is needed. O! had

I the ability, and could reach the nation's ear, I would, to-day, pour out a

fiery stream of biting ridicule, blasting reproach, withering sarcasm, and stern

rebuke. For it is not light that is needed, but fire; it is not the gentle

shower, but thunder. We need the storm, the whirlwind, and the earthquake. The

feeling of the nation must be quickened; the conscience of the nation must be

roused; the propriety of the nation must be startled; the hypocrisy of the

nation must be exposed; and its crimes against God and man must be proclaimed

and denounced.

What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer; a day that reveals

to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to

which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your

boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity;

your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciation of tyrants,

brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery;

your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious

parade and solemnity, are, to Him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and

hypocrisy -- a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of

savages. There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices more shocking and

bloody than are the people of the United States, at this very hour.

Go where you may, search where you will, roam through all the monarchies and

despotisms of the Old World, travel through South America, search out every

abuse, and when you have found the last, lay your facts by the side of the

everyday practices of this nation, and you will say with me, that, for revolting

barbarity and shameless hypocrisy, America reigns without a rival....

...Allow me to say, in conclusion, notwithstanding the dark picture I have this

day presented, of the state of the nation, I do not despair of this country.

There are forces in operation which must inevitably work the downfall of

slavery. "The arm of the Lord is not shortened," and the doom of slavery is

certain. I, therefore, leave off where I began, with hope. While drawing

encouragement from "the Declaration of Independence," the great principles it

contains, and the genius of American Institutions, my spirit is also cheered by

the obvious tendencies of the age. Nations do not now stand in the same relation

to each other that they did ages ago. No nation can now shut itself up from the

surrounding world and trot round in the same old path of its fathers without

interference. The time was when such could be done. Long established customs of

hurtful character could formerly fence themselves in, and do their evil work

with social impunity. Knowledge was then confined and enjoyed by the privileged

few, and the multitude walked on in mental darkness. But a change has now come

over the affairs of mankind. Walled cities and empires have become

unfashionable. The arm of commerce has borne away the gates of the strong city.

Intelligence is penetrating the darkest corners of the globe. It makes its

pathway over and under the sea, as well as on the earth. Wind, steam, and

lightning are its chartered agents. Oceans no longer divide, but link nations

together. From Boston to London is now a holiday excursion. Space is

comparatively annihilated. -- Thoughts expressed on one side of the Atlantic are

distinctly heard on the other.

The far off and almost fabulous Pacific rolls in grandeur at our feet. The

Celestial Empire, the mystery of ages, is being solved. The fiat of the

Almighty, "Let there be Light," has not yet spent its force. No abuse, no

outrage whether in taste, sport or avarice, can now hide itself from the

all-pervading light. The iron shoe, and crippled foot of China must be seen in

contrast with nature. Africa must rise and put on her yet unwoven garment.

'Ethiopia, shall, stretch. out her hand unto Ood." In the fervent aspirations of

William Lloyd Garrison, I say, and let every heart join in saying it:

God speed the year of jubilee

The wide world o'er!

When from their galling chains set free,

Th' oppress'd shall vilely bend the knee,

And wear the yoke of tyranny

Like brutes no more.

That year will come, and freedom's reign,

To man his plundered rights again

Restore.

God speed the day when human blood

Shall cease to flow!

In every clime be understood,

The claims of human brotherhood,

And each return for evil, good,

Not blow for blow;

That day will come all feuds to end,

And change into a faithful friend

Each foe.

God speed the hour, the glorious hour,

When none on earth

Shall exercise a lordly power,

Nor in a tyrant's presence cower;

But to all manhood's stature tower,

By equal birth!

That hour will come, to each, to all,

And from his Prison-house, to thrall

Go forth.

Until that year, day, hour, arrive,

With head, and heart, and hand I'll strive,

To break the rod, and rend the gyve,

The spoiler of his prey deprive --

So witness Heaven!

And never from my chosen post,

Whate'er the peril or the cost,

Be driven.

The Life and Writings of Frederick

Douglass, Volume II

Pre-Civil War Decade 1850-1860

Philip S. Foner

International Publishers Co., Inc., New York, 1950

| African American Spirituals A National Treasure | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

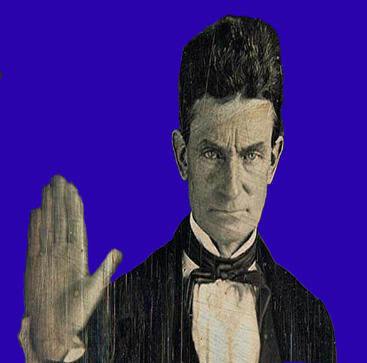

| William Lloyd Garrison | Frederick Douglass | John Brown |

| African American Spirituals |

| A National Treasure |

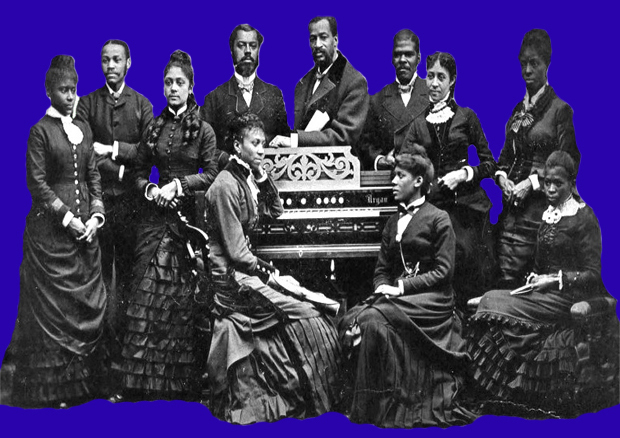

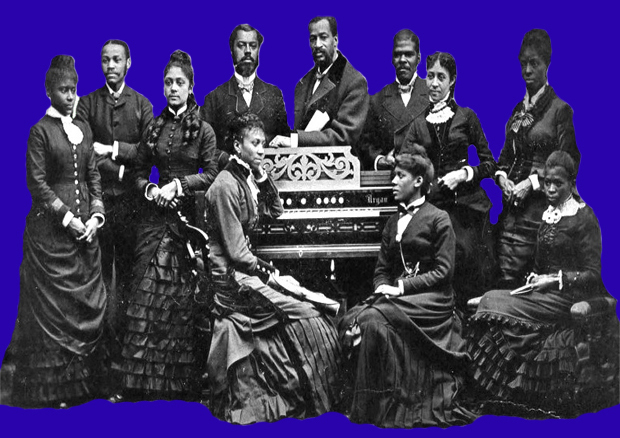

From 1619 to 1865, enslaved African Americans created their own unique form of expression known today as African American Spirituals. As African Americans were not allowed to speak their native languages or play African instruments, African American Spirituals incorporated into the English language and the Christian religious faith.

Simply defined, African American Spirituals are the songs created and first sung by African Americans during the times of slavery. These songs are celebrated as a American National Treasure. For they are the source for which gospel, jazz and blues evolved.

The lyrics of these songs are tightly linked with the lives of their authors who were inspired by the message of God and the gospel of the Bible. The most pervasive message conveyed by African American Spirituals is that of an enslaved people for yearning to be set free. The slaves believed they understood better than anyone what freedom truly meant in both a spiritual and a physical sense.

The Old Testament scriptures that are referenced in their songs spoke of deliverance in this world and they believed God would deliver them from bondage. These spirituals are different from hymns and psalms because the African American slave used them as a way of sharing the hard condition of being a slave while also singing about their love and faith in God.

The African American slave was forbidden to learn how to read and write. They had to find ways to communicate secretly. African American Spirituals were a medium for several layers of communication and meaning

African American Spirituals where the strong oral tradition of songs, stories proverbs and historical accounts. African American Spirituals have been apart of American culture from times of slavery to today and their legacy is clear in today’s gospel music. African American Spirituals where also sung during the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960’s. Songs that we are familiar with such as "We Shall Overcome" and "Marching Round Selma were heard in the south to united African American in the struggle for civil rights.

Some of the more commonly known songs including "Swing Low Sweet Chariot" and "The Gospel Train", used language which described activities but had a second meaning relating to the underground railroad.

The lyrics used in African American Spirituals became a metaphor from freedom of slavery and they were a secret way for slaves to communicate with each other, teach there young, record there history and heal there pain.

Frederick Douglas a fugitive slave who became one of the United States leading abolitionist stated that African American Spirituals told a tale of woe which was all together beyond feeble comprehension and that every tone was a testimony against slavery and a prayer to God for deliverance from chains.

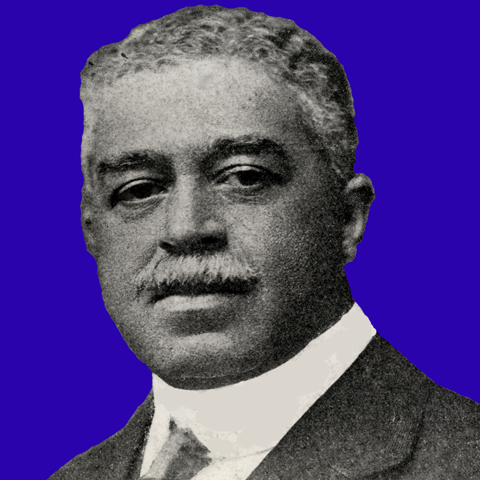

| Harry T Burleigh |

| December 2, 1866 to September 12, 1949 |

African American Classical Composer, Arranger and Professional Singer

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Harry T Burleigh

For more than 200 years, slavery was legal in the present boundaries of the United States. A country founded on the belief that all men are created equal with the God given right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. With one third (1/3) of its populations living in slavery, the United States would partake in one of history great ironies. Its incarcerated inhabitants, a nation enslaved would write the countries first folk music and sing the nations first songs of freedom.

Millions of voices and centuries of toil will rise up and become one voice and that voice will create a musical genre to which all American songs could trace their lineage and their roots.

Although his name is relatively unknown, Harry Thacker Burleigh (named Henry after his father) born on December 2, 1866 in Erie Pennsylvania.

Music was everywhere in the Burleigh’s home. His father Henry Burleigh who died when Harry was a child would lead the family in singing while they worked. His grandfather formerly enslaved was the town crier and lamp lighter and would take Harry and his older brother Reginald with him on his nightly rounds. Grandfather and grandsons would sing the songs of the African slave. The songs that the grandfather’s father and his grandfather sang songs of life and freedom.

Harry’s mother Elizabeth Burleigh and her sister Louisa taught him the songs of the European classical tradition. Elizabeth Burleigh was a college-educated woman fluent in both French and Greek. But in the early days of emancipation she was only able to get a job as a janitor and housemaid. She and her son Harry worked in the home of Elizabeth Russell a local arts patron who hosted performances of art songs. Young Harry would listen from a distance and the songs and singers he heard in Elizabeth Russell’s home help release his inner voice. A deep and rich baritone voice that was soon in demand at churches synagogues and homes in and around Erie Pennsylvania.

In 1892, Harry T Burleigh left Erie Pennsylvania to pursue a musical career. With only a few belongings an a head full of music, Harry T Burleigh traveled to New York City to audition for the National Conservatory of Music.

The years Harry T Burleigh spent at the Conservatory greatly influenced his career mostly due to his friendship with Antonin Dvorák the Conservatory’s director. After spending countless hours recalling and performing the African American Spirituals that he had learned from his grandfather, Harry was encourage to preserve these songs in his on arrangements and their themes could be heard in Antonin Dvorák’s new world symphony.

Before the turn of the century Harry T Burleigh established himself as a composer of popular art songs. For decades Harry T Burleigh traveled the world performing the songs of his grandfather all the while giving his country it’s first song which became jazz, swing, blues and eventually rock.

Harry T Burleigh died on September 12, 1949 and was buried in Erie Pennsylvania.

| Harry T Burleigh |

| December 2, 1866 to September 12, 1949 |

African American Classical Composer, Arranger and Professional Singer

African American Spirituals Videos

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| African American Spirituals |

| Instrumentals |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| African American Spirituals |

| A National Treasure |

| African American Spirituals A National Treasure | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

| William Lloyd Garrison | Frederick Douglass | John Brown |

Buy African American Spirituals

| African American Spirituals |

| A National Treasure |

| African American Spirituals A National Treasure | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

African American Spirituals © 2014 - 2024 All Rights Reserved |

African American Spirituals A National Treasure |